Cities Are Tearing Down Their Expensive Highways — Here’s What They’re Turning Into

MAY 6 2018 | LEANNA GARFIELD | BUSINESS INSIDER | POSTED WITH PERMISSION

Throughout the 20th century, highways were key generators of economic growth for American cities. They allowed commuters to quickly travel between urban centers and the suburbs, unclogged traffic-ridden streets, and created infrastructure jobs.

But these days, investing in highways is a bad business decision for many cities.

An increasing number of cities around the US are choosing to tear down or transform parts of their dilapidated interstates, rather than repair them. These redevelopments are largely happening because old highways are costly to rebuild, according to Rob Steuteville from a DC-based nonprofit called the Congress for New Urbanism.

For the past decade, Steuteville's team has documented cities that have or are considering highway removals. He expects the trend to continue to grow.

Take a look below:

When cities tear down parts of highways, they often transform them into boulevards, parks, and housing.

The Tom McCall Waterfront Park was created after the removal of the Harbor Drive Expressway in Portland, Oregon. Wikipedia Commons

Rochester, New York demolished nearly a mile of I-490, locally dubbed the Inner Loop, in late 2017.

Rochester's Inner Loop before it was torn down. Reconnect Rochester

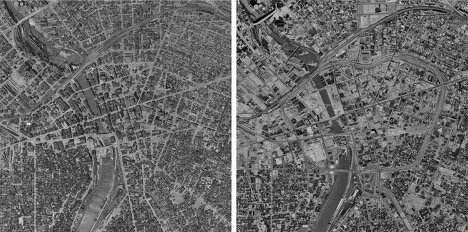

The highway used to sever downtown Rochester on all sides, as seen in these aerial photos which show the city before and after the Inner Loop's construction:

Aerial shots of downtown Rochester before the Inner Loop (1951, left) and after (1969, right). HistoricalAerials.com

In 2016, the city received a federal grant of $17 million for the $22 million removal project. The city is now eyeing a handful of redevelopment proposals, including ones for apartment buildings, retail stores, a museum expansion, and a hotel.

A proposed redevelopment of the former Inner Loop site in Rochester, New York. Urban Design Associates

Milwaukee, Wisconsin embarked on a similar project in 2002.

Milwaukee tears down its highway, starting in 2002. Milwaukee Department of City Development

An unfinished highway, called the Park East Freeway, was replaced with a landscaped, walkable boulevard. The city also created three new neighborhoods and a promenade district surrounding the highway's former site.

The Riverwalk in Milwaukee. Urban Land Institute

Boston's Central Artery was torn down to make way for the Rose Kennedy Greenway and other parks. Construction lasted from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s.

The Central Artery in Boston in 2003 (top) vs the Rose Kennedy Greenway in Boston in 2016 (bottom). AP/Michael Dwyer

Another earlier example is San Francisco's Embarcadero Freeway. Two years prior to its demise in 1991, the Loma Prieta earthquake damaged the freeway, and the city voted to demolish it rather than repair it.

The Embarcadero Freeway in San Francisco, California, 1982. Wikipedia Commons

Today, the area (still called the Embarcadero) is a wide, palm-lined boulevard with light-rail tracks in the median. A former on-ramp was also redeveloped into 75 low-income housing units.

The Ferry Building is a terminal for ferries on the Bay and an upscale shopping center on the Embarcadero in San Francisco, California. Wikipedia Commons

The Ferry Building is a terminal for ferries on the Bay and an upscale shopping center on the Embarcadero in San Francisco, California. Wikipedia Commons

Reasons for highway demolitions vary by city, but Steuteville said a common reason is that aging interstates are expensive to maintain.

The shoulder and one lane of westbound Highway 50 are damaged due to storms near Pollock Pines, California, Feb. 21, 2017. AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli

Counties across the US are dealing with roads and highways that need significant repairs. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers' most recent Infrastructure Report Card, one out of every five miles of highway pavement is in poor condition.

For many cities, it's often cheaper to level the street grid than repair highways. And when neighborhoods remove freeways, real-estate values increase.

The proposed Green TI, parkland served by a small road, would replace a mile of the Terminal Island Freeway in Long Beach, California. Meléndez/CNU

Most of the nation's highways were built after World War II in an era of economic prosperity and rapid suburban development.

Robert Moses, right, chairman of Mayor Robert Wagners Slum Clearance Committee, with New Haven, Conn. Mayor Richard Lee, March 4, 1958, Randalls Island, N.Y. AP

In 1956, the Eisenhower administration enacted the Federal-Aid Highway Act, which gave cities $25 billion to construct 41,000 miles of the Interstate Highway System over the next decade. For each highway project, the federal government covered 90% of the costs.

Some cities, like Kansas City, Missouri and Syracuse, New York, built interstates right through their downtowns. It seemed like a good idea at the time.

I-81 in Syracuse, New York today. CNU

"This was a program which the 21st century will almost certainly judge to have had more influence on the shape and development of American cities, the distribution of population within metropolitan areas and across the nation as a whole, the location of industry and various kinds of employment opportunities," the late Senator Daniel Moynihan wrote in 1970 about the federal program.

But in reality, highways — especially ones that cut through downtowns — did more harm than good to urban areas.

The first concrete was poured on a section of interstate 65 in Hardin County, Kentucky, May 27, 1959. AP

They displaced largely low-income communities, segregated neighborhoods, increased the amount of air and noise pollution, contributed to poverty, and devalued surrounding properties.

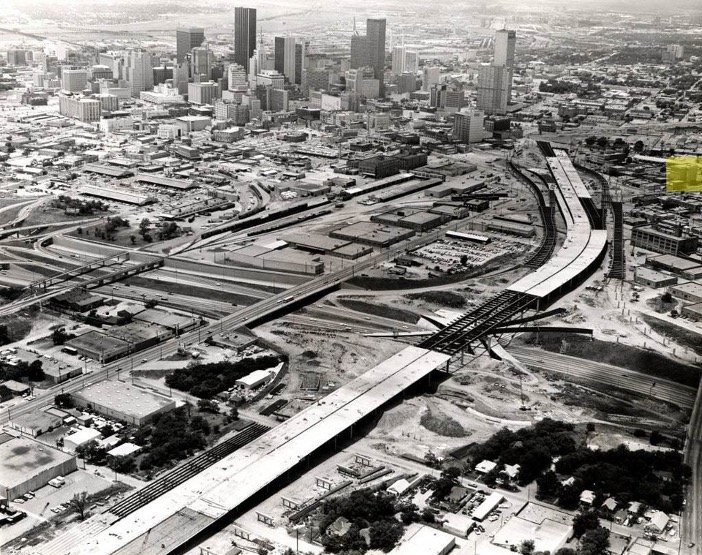

Construction of Dallas' I-345 in the early 1970s, cutting off Deep Ellum from downtown. AIA Dallas

Highways really cut off connectivity," Steuteville said. "What makes cities valuable is that they connect people and economies. And what highways do when they cut through cities is divide."

Overall, these highways encouraged sprawl. Residents who flocked to suburbs took tax revenue with them, and cities struggled to come up with revenue for schools, mass transit, and other city services.

Sunday traffic from New York City to the Jersey Shore in 1941. Library of Congress

There's also growing evidence that widening an existing highway doesn't reduce congestion. Instead, it encourages more people to drive in a phenomenon known as induced demand.

Several highway sections across the US will soon see the end of the road. New Haven, Connecticut, is working on a project called Downtown Crossing, which has demolished parts of Route 34 and is constructing buildings in an area once bisected by the freeway.

A rendering of the proposed New Haven development. Newman Architects

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo recently announced that Albany will convert a ramp that goes to Highway 1-787 into a car-free park for pedestrians and cyclists as well.

A rendering of the Albany Skyway. Capitalize Albany

And Somerville, Massachusetts has committed to replacing the McGrath Highway with a surface-level boulevard, slated for construction from 2026 to 2029.

A rendering of Somerville's McGrath boulevard. CNU

The growing movement to tear down freeway infrastructure symbolizes the nation's changing attitudes about what future cities should look like.

Robert Moses' proposal of the Lower Manhattan Expressway in 1961 that was blocked by Jane Jacobs. Museum of the City of New York

Part of the traditional American dream, after all, is owning a car. Novelist J. G. Ballard wrote about America's obsession with the automobile and the highway in 1971.

A rendering of a revitalized Seattle waterfront. Rethink 81

"If I were asked to condense the whole of the present century into one mental picture, I would pick a familiar everyday sight: a man in a motor car, driving along a concrete highway to some unknown destination," he wrote.

"Almost every aspect of modern life is there, both for good and for ill — our sense of speed, drama, and aggression, the worlds of advertising and consumer goods, engineering and mass-manufacture, and the shared experience of moving together through an elaborately signaled landscape."

Their destruction could transform American cities as we know them.

Alaskan Way Viaduct today in Seattle, Washington. DJC.com